Introduction to AMD Freesync

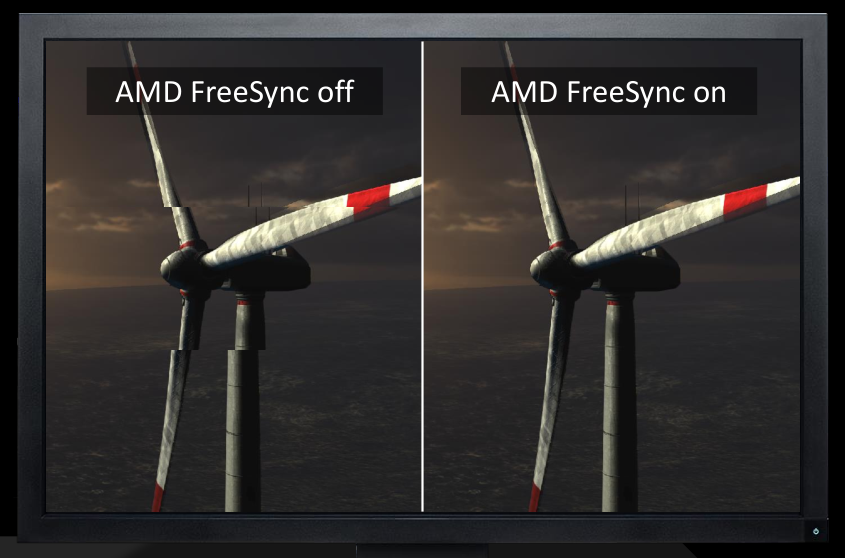

Modern gaming spawned three problems through the course of advancements we received over the years; screen tearing, input lag, and stutter. In layman’s terms, this flaw happens when your screen scans in cycles at its fixed rate, and the GPU is unable to draw frames to fill or match the spot in 1 cycle. This results in a split in the image while in action, prominently seen in graphics-intensive titles such as The Witcher 3 or quick-paced games such as Overwatch. All three problems are related to each other, and V-Sync, one of the first solutions implemented did solve the first issue, but not without a cost.

This first technology smoothes out the image in games, but at the expense of added input lag. Reaction times and the connective feel when swiping that crosshair to chase your foe significantly degraded, so V-Sync was at the most, only half of a total solution.The problems with V-Sync are caused by its attempt to match the different frames of your game produced according to your graphics card‘s power with your monitor’s fixed refresh rate. Simply put, the two parts are waiting on each other to display sequential frames, and the time involved is then added as input lag and seen as stutter on screen or felt like a delay between your control input and the picture on the screen.

After some time in 2013, Nvidia releases their variable refresh rate technology called G-Sync. The technology was a godsend for gamers because instead of forcing the last frame to wait for the next refresh cycle, G-Sync harmonizes the two by letting the monitor’s refresh rate go slower or faster depending on how many frames your GPU is producing cutting away the input lag and stutter. This addition, however, does come at a high cost, since Nvidia requires proprietary modules installed into monitors and licensing for their use plus exclusive compatibility, segregating a huge chunk of the gaming population who rely on AMD products.

Of course, the red team soon responded with a solution of their own, which provides the same result as G-Sync using different methods of implementation, no licensing or exclusivity, and no additional hardware leading to no other costing for each certified display product. This train of thought is where the word “free” in Freesync is derived. Certified products cost around $200 less than the competitor’s offering, and currently, there are almost three times as much available which are capable and compatible with Freesync.

Freesync Implementation, Benefits, and Downsides

Freesync is based on the Adaptive-Sync, a free standard by VESA and readily implemented and included in the DisplayPort 1.2a specifications and recently, with HDMI 2.0 as well. The display controller for Freesync is integrated into some of the latest AMD video cards, so there are no added costs of redesigning, manufacturing and calibrating external modules which install into the monitor’s PCB. Controlling the synchronization of the display with the GPU’s FPS output is achieved with the latest Freesync-enabled drivers, so manufacturers do not have to worry about factory adjustments for which usually differs from unit to unit. Users, on the other hand, only need a newer GPU which has the mentioned controller in its innards, download the latest drivers, and then connect the monitor and activate Freesync.

As noted, the price tag of Freesync monitors are considerably lower than their G-Sync variants, and some of the biggest examples of this are the Asus MG278Q and the PG278Q. Both are excellent products in our book, and concerning performance, and they are not far apart from the each other. Their biggest difference is in their VRR tech compatibility, a few minor cosmetic additions on the latter, and their I/O layout. The MG278Q goes for around $480 at the time of this writing; meanwhile, the other costs $200 more. The Nvidia-required control module on the PG278Q dictates the higher price, while also restricting the user to one signal input choice. This drawback also carries over to the software side of things, since G-Sync takes control of other settings such as brightness, color, and sound potentially disabling or limiting some of the monitor’s capabilities unlike in Freesync where the user is free to adjust these options accordingly.

Aside from the methods, Freesync’s variable refresh rate functions from 9Hz to 240Hz, but only in increments. We don’t have monitors that are capable of those numbers, but usually, we see fixed scopes like 48Hz to 90Hz or any range in between 9Hz to 240Hz. G-Sync on the other hand functions at 30 to 144Hz. At a fundamental viewpoint, Freesync is more practical since the problems this tech aims to solve are prominent at rates nearing the lower half of a gaming monitor’s maximum refresh rate. Although it is interesting to note that there are newer products capable of ranges reaching 144HZ, like the BenQ Zowie XL2730, which as a 40Hz to 144Hz effective range. If your PC build is capable of high FPS output, tearing would be the least of your concerns as far as picture quality goes. Another advantage of Freesync is it allows users to choose whether to let V-Sync take over once your FPS dips below or extends beyond the particular range an individual product is capable with. If your frames drop below the minimum, tearing will ensue since the monitor will revert to its maximum refresh rate, or otherwise, if V-Sync is on, you will experience input lag. If it were me, I would still choose to leave V-Sync off and live with the tearing, since the induced input lag is a bigger bother than minor image defects which would only last less than a second.

Also, when frames are down below the specified minimum threshold, G-Sync would automatically deactivate and leave everything to V-Sync, producing nightmarish stuttering and input lag, capable of ruining that split second action in your gaming session. AMD has a better solution in the form of LFC or Low Framerate Compensation. This tech uses reuses the last frame displayed when your FPS drops below the minimum range, filling the missing gap. The concept is easy to understand and similar to Nvidia’s frame doubling solution, but tough to implement since the GPU will need to able to predict the next frame. AMD states that they have a custom algorithm to help with this challenge, which is included in the latest drivers and utilities. One caveat of this feature is it requires a product to have a maximum refresh rate 2.5 times the minimum (For example, 40Hz – 100Hz) to function. Products like the LG 27UD68-P with 40Hz to 60Hz Freesync range cannot take advantage of this feature.

Thoughts and Reactions

Out of the two VRR solutions we have, AMD’s Freesync is without a doubt the practical choice between the two. You can enjoy its benefits without spending an extra chunk of cash, and you probably would not need to buy a newer monitor when AMD pushes out upgrades to the already magical capabilities of this feature since changes will be added through newer drivers or utilities instead of ameliorated hardware. Monitors usually outlast two to three new CPU builds, so investing in peripherals that ages admirably is the best decision you can make. One thing we hate about these features is that currently, they are exclusive to each brand. The two solutions require GPU products from the same company, so one isn’t compatible with the other.

Nvidia is the leading proponent of this divide since they now won’t allow other companies to modify or study their tech while requiring partners to submit to their licensing fees and proprietary hardware and calibration. AMD Freesync, on the other hand, is somewhat, open source, since the VESA standard it is based on is also free. This thought makes Freesync the ethical choice for gamers. Although in fairness to the green team, they have expressed intent to share compatibilities with the competitor for the benefit of the gamers, if there is enough demand. Some signs prove that Nvidia is investigating alternatives to the need of proprietary hardware for their tech to function. G-Sync laptops can somehow prove this, since these mobile gadgets do not have control modules, but VRR is functional in the system.

Freesync is a great tool to solve one of gaming’s oldest and most prominent issues. There are limitations up to the time of this writing, but judging from the progress AMD accomplishes regarding adapting solutions to evolving needs, we will surely see Freesync in a fully developed state. But of course, our biggest wish is cross compatibility between this tech and G-Sync, so gamers can enjoy all the benefits whether they are on the red or green team. But for now, if you decide to jump on the AMD wagon, and enjoy what their VRR solution has to offer, rest assured that your choices are not limited. A lot of the top display products are Freesync certified, and owning them is easier thanks to the bloat-free price tags.

Check out Our Best Freesync Monitors Guide

Leave a Reply